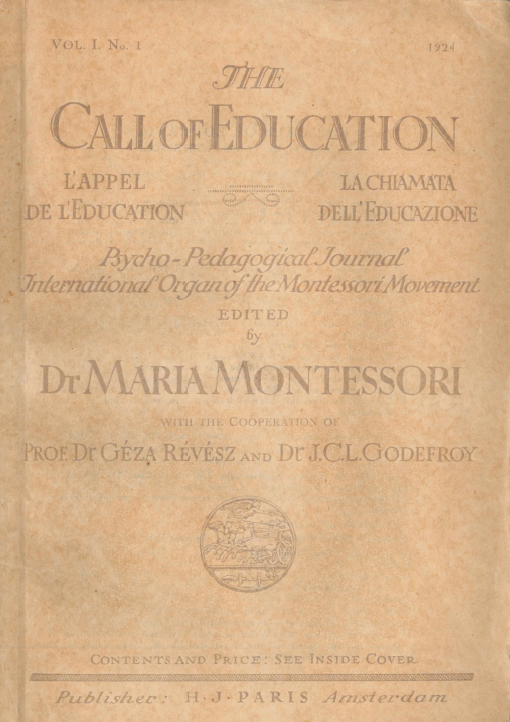

"The Call of Education: Psycho-pedagogical Journal" represents the initial endeavor of the Montessori movement to establish an international communication platform. It is a multilingual journal featuring articles in English, French, Italian, and German. Three issues were released in 1924, followed by an additional three in 1925. The first two issues were published by H.J. Paris, while the latter three were overseen by Van Holkema en Warendorf, which included several Montessori titles in its catalogue. It's important to note that a formalized international organization did not yet exist: the AMI was founded only in 1929 and headquartered in Amsterdam from 1935 onwards.

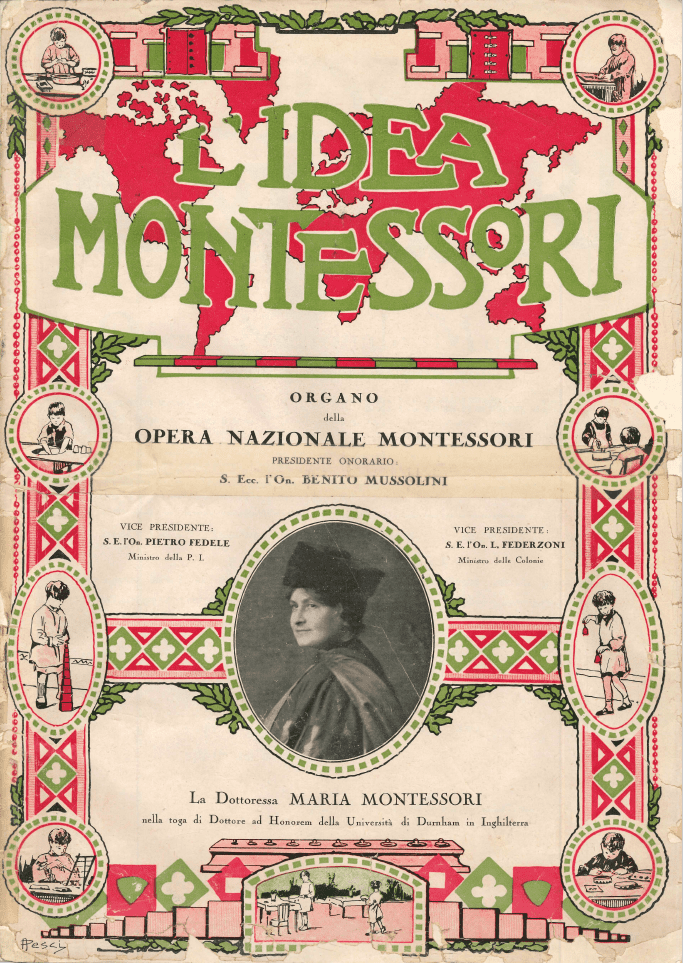

The Dutch city has been a part of Montessori's influence since 1914 when Jo Werker established an initial educational service after attending a course in Rome, followed by Montessori's first visit. By the winter of 1923-1924, Montessori had already made her fourth visit, a prolonged stay dedicated to training new educators. Acknowledged with all honors by the authorities, she also traveled to the United Kingdom to receive an honorary degree from the University of Durham on December 11, 1923. All these events are duly documented in the inaugural issue of the journal, which emerged almost as a celebration of Amsterdam's recognition as the international hub of the movement.

Within its first decade, Montessori's presence in the Netherlands had significantly expanded and diversified. It engaged with the typical manifestations of the country's cultural pluralism reflected in its educational and school institutions. Montessori found a receptive audience, resonating with the sensibilities of various ideological backgrounds, including liberal, social democratic, secular, Catholic, or Protestant affiliations. As early as the 1920s, part of the local elite in Amsterdam received education in a Montessori lycée. The municipal elections of 1919 introduced the first female councilors, predominantly from the Social Democratic Party, many of whom had a specific focus on educational services in their political careers, demonstrating sympathy for the Montessori approach and advocating for its expansion to working-class families through a network of public services.

This context was already stimulated by the transnational dynamics of the Froebelian movement, where the circulation of new educational models had enduring political and cultural implications. The pedagogical mobilization of the local bourgeoisie gravitated towards Montessorianism, allowing for a dialectical approach (for a reconstruction of the context, see Schirripa, Una rivista internazionale per il movimento montessoriano: The Call of Education 1924-25, in “Educació i Història: Revista d'Història de l'Educació”, 40, 2022, pp. 55-81; Christine Quarfood, The Montessori Movement in Interwar Europe. New Perspectives, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2022).

In The Hague, for instance, a more eclectic Montessori nucleus emerged, open to comparisons and hybridizations with other contemporary pedagogical innovations, such as the Decrolyan approach from neighboring Belgium: in 1924, Ovide Decroly himself wrote about it in "Pour l'ère nouvelle," a journal of the Ligue internationale pour l'éducation nouvelle, announcing the birth of "The Call of Education" as an expression, instead, of the core of the closer Montessori observance present in Amsterdam.

Furthermore, the traditional role of the Netherlands as a haven for exiles from across Europe was experiencing a new phase, politically unfavorable yet culturally fertile. One of the two scientists who joined Montessori as co-editors of the journal was Géza Révész (1878-1955), representing Hungarian Jewish intellectual emigration after the rise of the Horty regime - in 1932, he acquired citizenship and became the first chair of Psychology at the University of Amsterdam.

His is a family of intellectual exiles (his wife being Magda Alexander, an art historian and daughter of the philosopher Bernhard) who will find channels of expression in Montessorism (including the journal) and integration into the host society. The other is Jan Carel Lodewijk Godefroy (1883-1957), also a psychopathologist, active in the theosophical movement, married until 1931 to Maria Remmina van Mill (1884-1979): in the journal, she is attributed an ancillary role, but she will be the most prominent figure in the Dutch Montessori movement among the three.

"The Call of Education" is a reference point for examining how Montessorism becomes a movement, activating a social fabric particularly inclined to identify in the commitment to modern and child-friendly education a duty connected to social status, following the tradition of the eighteenth and nineteenth-century pedagogical movement. The pages of the journal lend themselves to be used as an index of the nodes within an international network where multiple affiliations intersect, with a stratification between the Montessori world and additional contributions – for instance, the professional interlocutors of the two co-editors who are not all internal to the movement but collaborate with interest on the journal. These scientific contributions, even when juxtaposed with the pedagogical issues of the Montessori world without engaging in much dialogue with it, underscore an accreditation that supports the movement from the outside, complementing the efforts of the editors in providing educators with models of pedagogical practice and disseminating news from Montessori institutions worldwide.

We express our gratitude to the Association Montessori Internationale (AMI) and the Maria Montessori Archives (Amsterdam) for making available the 1924 issue 3-4 of "The Call of Education" (https://montessori-ami.org) and for their support in our research endeavors.

Credits: Vincenzo Schirripa